Can we define the 'f-word' famine?

Throughout this blog I will be assessing the interconnected issues of water and food in Africa. The focus will be on dissecting western imaginaries surrounding Africa whilst also understanding the relationships modern day technology is having on changing food production. Food production would be nothing without water.

My choice of topic for this blog largely comes

from studying Human Ecology and Development which investigated the relationships

between famines and water scarcity. Also, coming from Bangladesh, the stories of

the 1974 famine has always been circulated with different narratives, some elders

recall the famine as being a time of no food whilst my grandmother recalls the

famine not directly caused due to lack of food but because of political

unrest and colonial powers over rice grains. These narratives around

water and food piqued my interest into the African context since the largest

famines in the 21st century have been in the African continent. The real

question is, whilst famines on this scale have reduced in other parts (demonstrated

by the figure) of the world why do famines persist in Africa?

I question if there could be a single reason as to why famines persist, every famine has its own context and nuances behind the political discourses, but it would be a mistake to confuse water scarcity as the sole cause of famines in Africa. Before the mid-twentieth century the cause of famine was accepted as the decline in food availability (Rangasami,1985) yet this idea is largely contested today. Especially when looking at the three recent African famines in Ethiopia, Niger and Malawi where erratic weather conditions was the final straw that tipped livelihoods over the edge (Devereux,2009). The economic situation and failure of the markets to deliver food at an affordable price was a significant factor in what led to these famines. Sens’s work was a large contribution which moved away from the Malthusian logic of “too many people, too little food” (Edkins,2000) to the entitlement approach which questioned what a household could get access to (Sen,1999). Whilst this did change the perception of famines it failed to see famines as a political crisis, an economic shock as well as a natural disaster. If we look only a year ago the South Sudan famine was caused by both ongoing civil war and the climate. Below the VOX video highlights how famine can be used as a political tool in warfare.

What can we learn from this constant revisiting of the “f word” and changing definitions? Academics have contested definitions of famine in every aspect yet have never come to an agreement which leads me to question whether there can be a single definition of a famine. Yes, a definition may help in holding governments accountable as some refuse to declare famine for political reasons, however I do not agree with the sentiment that academics should be racing for a definition of famine to be found but rather a definition should be agreed (Howe and Devereux, 2004). The theory of a famine in terms of economics, politics, climate as well as historical context is the groundwork in understanding a famine and it must be used to act but more importantly this theory must be used to prevent famines before they occur.

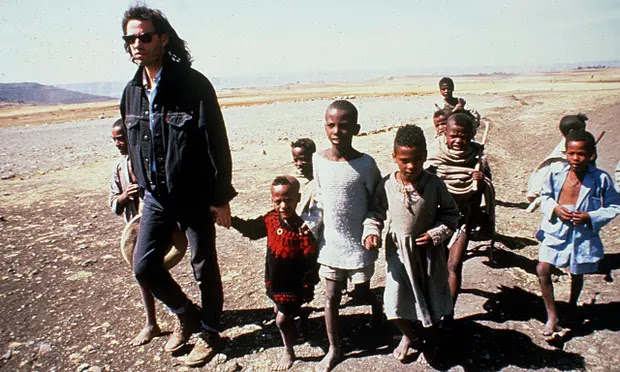

A famine cannot be viewed in isolation but rather the histories at play and the development of

the famine must be examined holistically. The next blog will be a further exploration into famines, a deep

dive into the Ethiopian famine in 1984 and the role of western imaginaries in

shaping visions of Africa.

Comments

Post a Comment